The History of the T

Boston might be the birthplace of the American Revolution, but did you know it’s also the birthplace of public transit in America?

It’s true! The first subway tunnels built in America are still in use today under the Boston Common, and people still take ferries into the city the way they did all the way back in 1631. Our trains and boats are much different now, but they’ve been an important part of our city for more than 300 years.

1600s

In the 1600s, Boston was just a peninsula, connected to Roxbury by a thin strip of land. To get to the city, farmers and residents in Chelsea had to walk through Malden, Cambridge, Brighton, and Roxbury. The journey took 2 days.

This was such a burden that the Massachusetts Court of Assistance offered a contract to anyone willing to run a ferry between the Shawmut Peninsula (now the North End of Boston) and Charlestown. In 1631, Thomas Williams opened the first chartered transit service in the United States.

While Boston proper is connected to surrounding communities by a number of bridges and tunnels today, many people still take the ferry from Boston to Charlestown, the Airport, Hull, and Hingham.

1700s

During Colonial times, few people could afford a horse and carriage, but most were able to travel the peninsula on foot—it was only 800 acres wide, after all. But after the Revolution, the population of the city grew rapidly, and other modes of transit became increasingly important.

The first stagecoach between Boston and Cambridge opened in 1793.

1800s

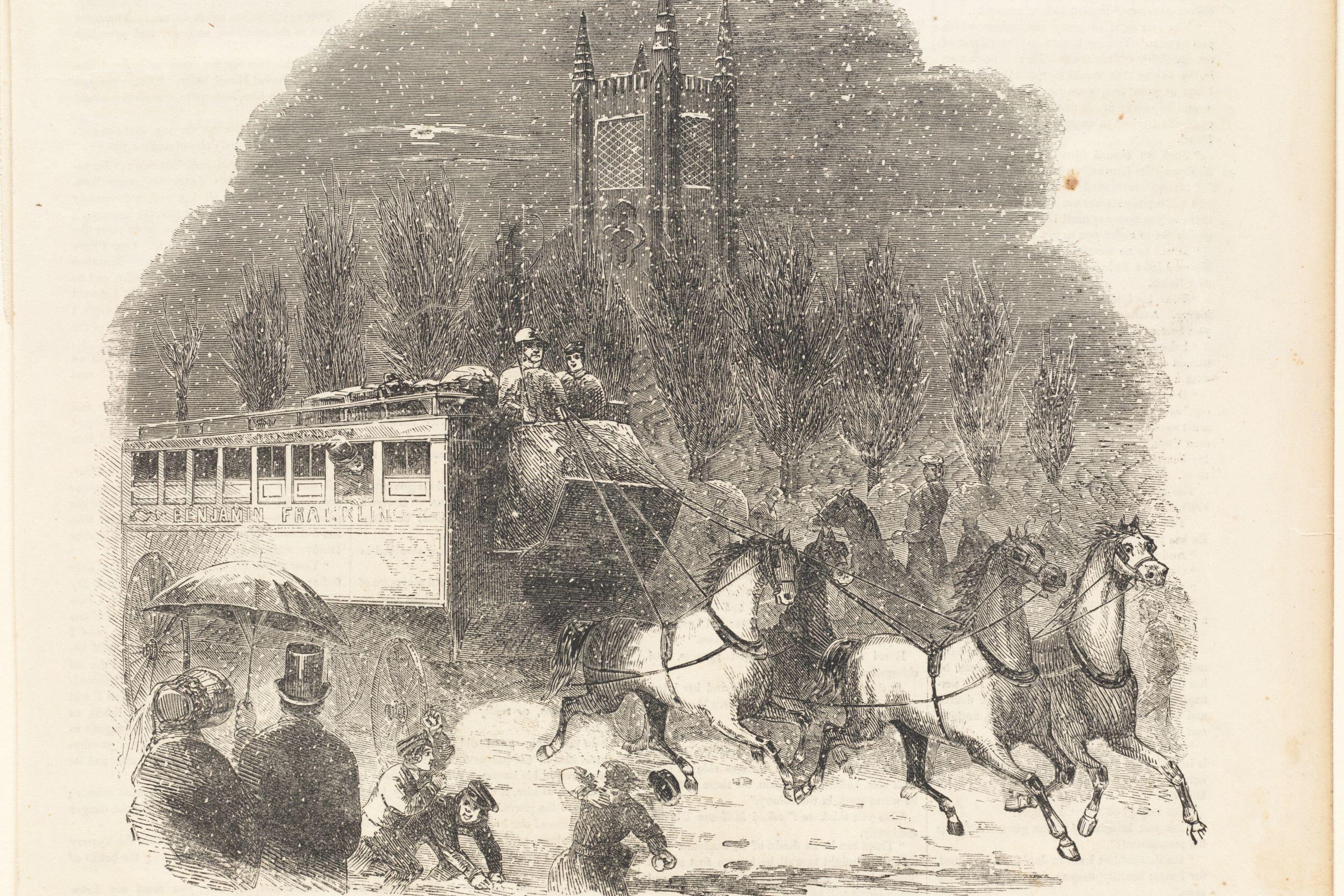

By the early 1800s, a larger, redesigned stagecoach, The Omnibus, became popular. It made multiple stops on predetermined routes, which made it reliable. But, because of Boston’s bumpy streets, it wasn’t a very comfortable ride.

Boston’s first horsecar on rails, which avoided the ruts of Boston’s streets, and could carry more passengers, operated between Central Square in Cambridge and Bowdoin Square in Boston beginning in 1856.

Old Billy and the Boston rails

In 1856, a horse named Billy began running for the West End Street Railway. Among the thousands of horses eventually ‘employed’ by horsecar companies, Old Billy was perhaps the most notable. Old Billy’s career as a car horse for the West End Street Railway lasted 25 years: having run over 125,000 miles on Boston’s rails.

Learn more about the West End Street Railway1880s

By 1887, more than 20 companies (and 8,000 horses!) provided horsecar service around Boston.

Bloated fares and fierce competition for customers led the General Court of Massachusetts to pass an act that consolidated all horsecar companies into the West End Street Railway. At the time, it was one of the largest street rail operations in America.

But horsecar travel had its own risks, especially when the horses became ill or were injured. The West End Street Railway began investigating alternatives in the late 19th century, taking inspiration from cable car lines in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles.

When a cost analysis showed that maintaining cable cars in cold weather would be expensive, because the cables ran underground, the West End Company halted plans for two cable car lines in Boston. As a last resort, the company visited the Union Passenger Railway Company in Richmond, Virginia, to see their railcars, which were powered by electrified copper wires that ran above the trains, rather than underground.

The West End Company and Boston’s City Council were so impressed, they debuted the city’s first electric streetcar on January 1, 1889, connecting the Allston Railroad Depot, to Coolidge Corner and Park Square. Today, the Green Line C Branch still travels this route.

1890s

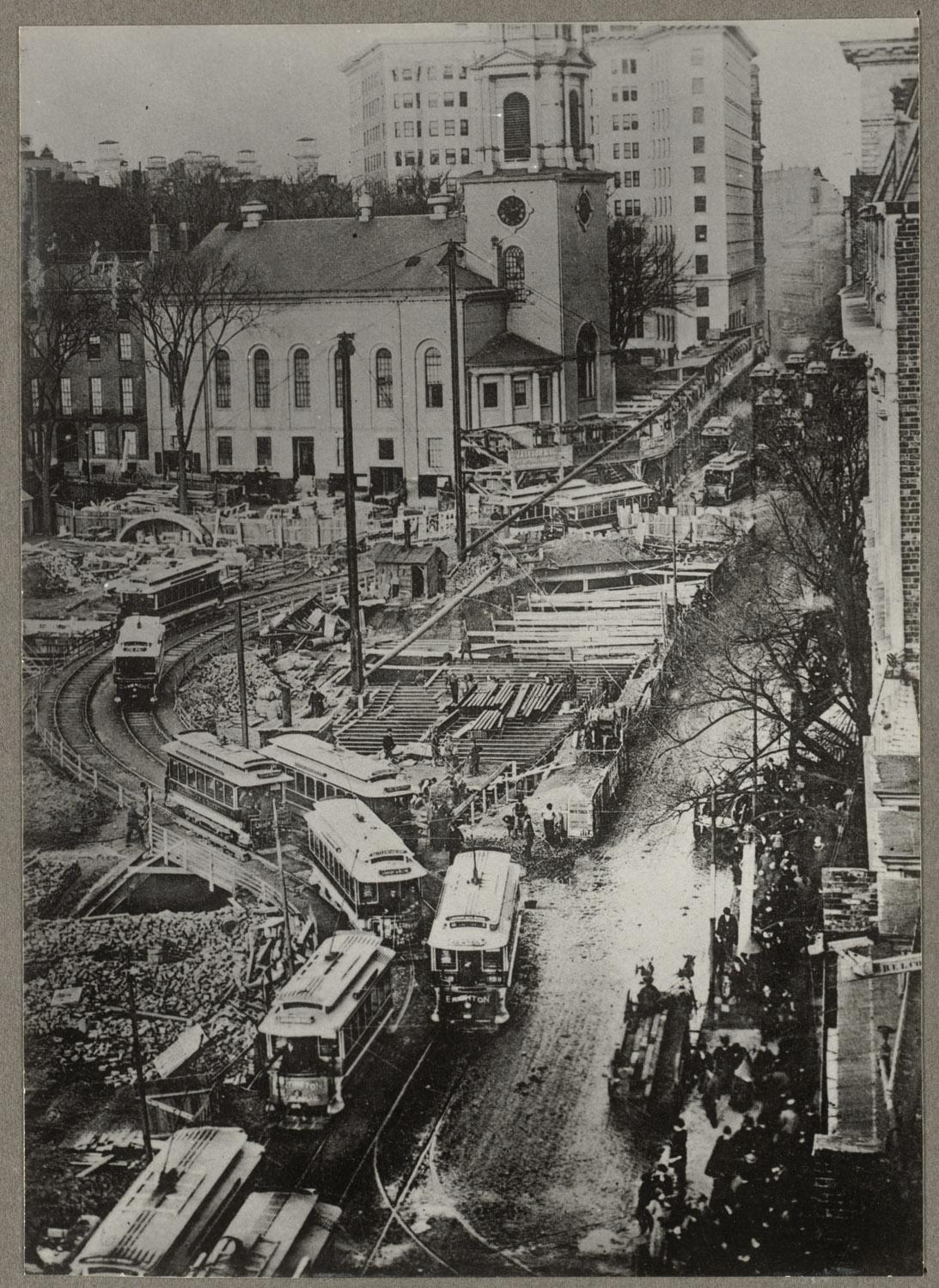

In the late 19th century, Tremont Street was so crowded, residents joked they could get to their destinations faster by walking along the roofs of their stalled streetcars.

In response, the Governor of Massachusetts and Mayor of Boston appointed the Rapid Transit Commission to investigate improvements to the system in July 1891.

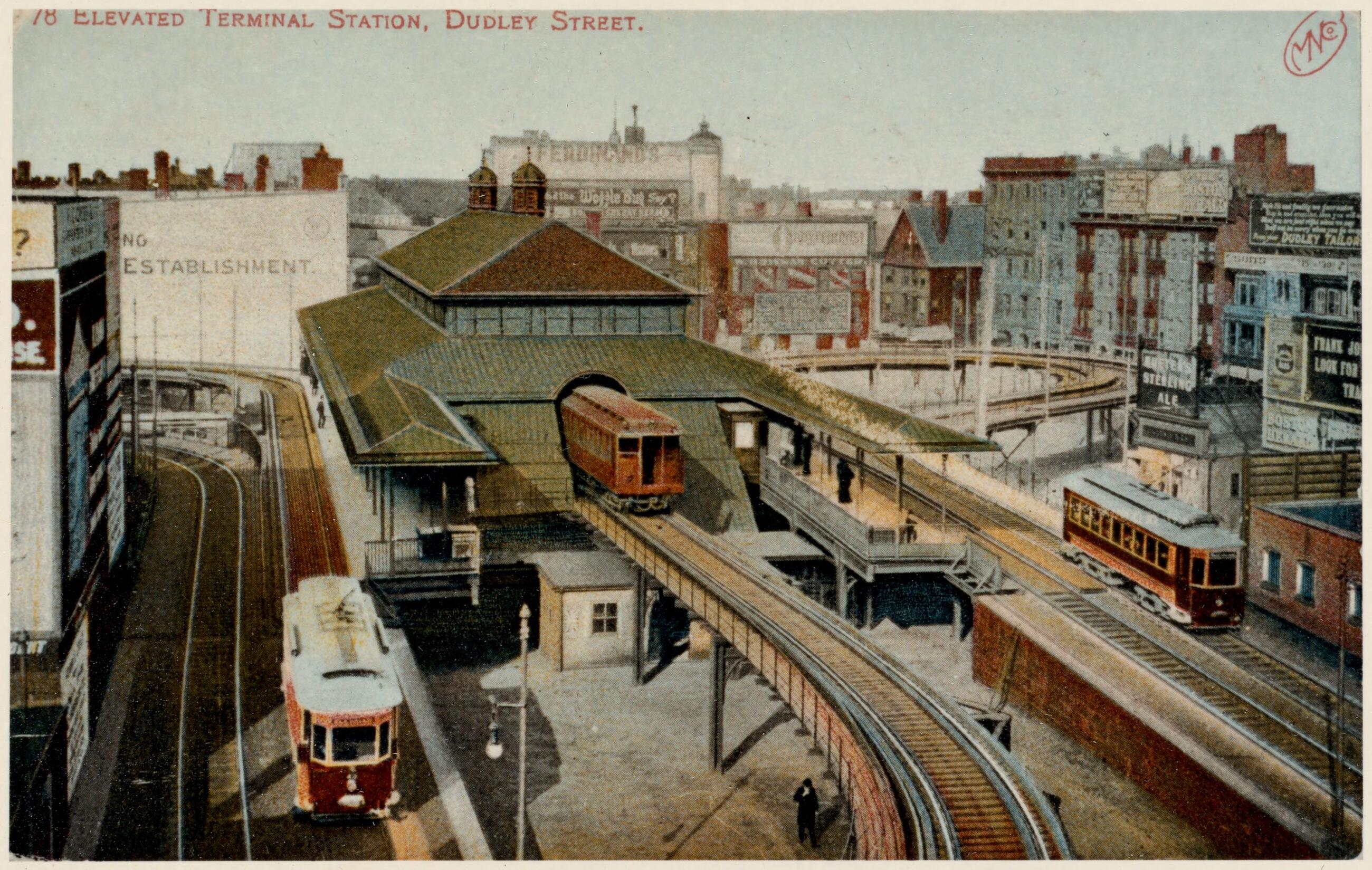

The commission recommended four elevated railway lines and a tunnel for streetcars under Tremont Street. They also authorized the creation of the Boston Elevated Railway Company (BERy), which would ultimately absorb the property of the West End Street Railway in 1897.

BERy was later absorbed by the MTA and then the MBTA, but it left a mark on Boston’s infrastructure in two big ways.

First, to help trains travel faster through Boston’s twisting, narrow streets, BERy joined together two, 20-foot streetcars in a way that would allow them to bend in the middle. Bostonians of 1913 called them “two rooms and a bath.” Today, we call them articulated cars, and they’re used for train and bus service all over the world—even here in Boston on the Green and Silver lines.

Second, the Tremont Street subway opened in 1897 as North America’s first subway tunnel. It’s still in use today, connecting Government Center, Park Street, and Boylston stations.

1900s

BERy faced financial struggles in 1918 that led to the General Court of Massachusetts passing the Public Control Act. The act provisioned a public Board of Trustees to set fares to cover the cost of public transit, allowed the board increase taxes in the 14 towns served by BERy, and compensated BERy shareholders through dividend earnings.

In 1947, the state legislature formed the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) to absorb BERy. The MTA then purchased all outstanding stock and stopped shareholder compensation. It was managed by three governor-appointed trustees and served the citizens of the original 14 towns in the Public Control Act.

In 1957, the MTA authorized the expansion of rapid transit along the Newton Highlands Branch of the Boston and Albany Railroad. Service on the Highland Branch began in 1959, and is still in operation today as the Green Line D Branch, with service between Boston and Newton, MA.

Charlie on the MTA

"Charlie on the MTA" was written as a campaign song for Mayoral candidate Walter A. O'Brien, Jr. in 1949. It tells the story of a subway rider named Charlie, stuck on an endless train ride underneath the streets of Boston because he was unable to pay the exit fare.

The last of the exit fares on the T were eliminated in 2006, but Charlie's endless journey lives on in the name of the T’s current fare system—the CharlieCard and CharlieTicket.

Listen to the song here1960s

During the 1950s and 60s, Boston’s business districts grew, as did the popularity of cars, congesting Boston’s streets and highways. In response, urban planners expanded the city’s highway system and parking complexes.

More commuters began taking the train into the city, and the MTA's debt grew as it faced increased demand. Though the train system was supported by an annual subsidy, suburban residents were concerned that any system expansion meant to ease congestion would increase debt, but wouldn’t improve the commute.

Legislators, community leaders, and urban planners conducted a massive study of transit needs in eastern Massachusetts. The result integrated the existing railroads of greater Boston into one comprehensive public transit system: The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA).

The MBTA, or the "T," was voted into law on August 3, 1964, becoming the first combined regional transit system in the U.S., serving 78 municipalities in the Greater Boston area. Like the MTA, the MBTA was formed as a state agency.

In 1965, the federal government’s newly formed Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA), now known as the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), provided the initial funding for the MBTA’s first modernization projects Copley, Maverick, Prudential, Columbia (now JFK/UMass), Orient Heights, Fields Corner, Government Center, Kenmore, Haymarket, and Arlington stations.

Additionally, funding from the UMTA helped the T legally reserve New Haven Railroad’s rail lines and rights-of-way for the development of the MBTA Commuter Rail.

Since 1965, the FTA has funded $3.5 billion in improvement projects at the MBTA.

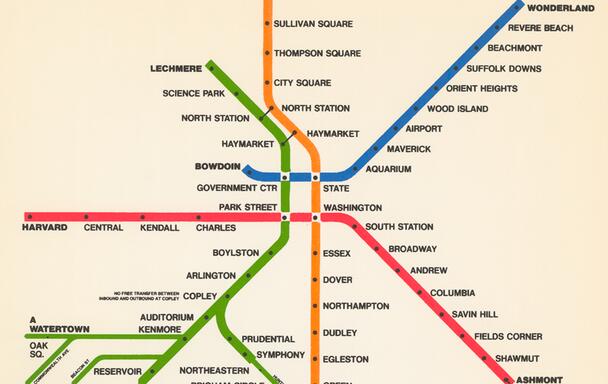

Colors of the Lines

After the consolidation of Boston area transit into the T in 1965, a local consulting firm was hired to make a rapid transit map. Rather than labeling the transit lines by the cities they served, the new map color-coded the lines. First, the consultants chose red, green, blue, and orange because of their ability to be easily distinguished from each other. Red was assigned to the line that terminated at Harvard University for its school color of crimson. The transit line that ran under the Boston Harbor was called the Blue Line.

Although there's a longstanding myth that all transit lines were branded because of their specific geography, according to the original consulting team, the branding of the Orange and Green lines was random.

View current maps1970s

Until the late 1900s, many residents in eastern Massachusetts considered public transit to be a supplementary mode of transportation. But in the 70s, a gas shortage, concerns over air quality, and urban congestion made the T more popular than ever, with more than 300,000 daily riders.

1980s

By December 1980, increased demand and funding shortages resulted in a 1-day shutdown. To avoid future shutdowns, the legislature approved the expansion of the MBTA board from five to seven members, including the Secretary of Transportation.

Seven years after its expansion, the board oversaw the completion of a $743 million dollar construction project. The Southwest Corridor Project demolished the elevated portion of the Orange Line —originally named the Washington Street Elevated — and relocated the affected stops.

After the construction of the Washington Street Elevated, Bostonians in the early 1900s were thrilled to avoid street-level traffic. However, nearly a century passed and residents began to view the elevated Orange Line, which ran from present-day Chinatown to Forest Hills, as a noisy eyesore. In May 1987, crews completed their demolition of the elevated Orange Line and riders celebrated the completion of nine new accessible Orange Line stations.

Accessibility at the MBTA

1990s

In 1990, the federal government passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) which required that public transportation be accessible. As a result, the system experienced a number of improvements – from several station renovations with new accessible vehicles to an expanded paratransit system.

2000s

Despite some early progress following the passage of the ADA, by the 2000s, riders with disabilities still could not safely or reliably access critical MBTA services.

In 2002, a group of riders filed a class-action lawsuit against the MBTA. Four years later, the parties entered into the Daniels-Finegold et al. Settlement Agreement. As a result of this settlement, sweeping changes to virtually every aspect of service improved accessibility and usability for all riders.

Today, the MBTA is recognized as one of the most accessible systems in the country.

In 2009, Governor Deval Patrick signed legislation that put the MBTA under the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT).

To address public concern over management and spending at the T, in 2015, Governor Charlie Baker appointed transportation, finance, and engineering experts to the Fiscal and Management Control Board (FMCB). The FMCB was formed to evaluate MBTA operations and met on a near-weekly basis until the expiration of its term in June 2021. A month after, the Massachusetts legislature established a permanent seven-member oversight board. Currently, this seven-member board of directors and an 11-member MassDOT Board oversee operations at the MBTA.

As of 2021, the T is the largest American transit agency to use electricity that is 100% produced from renewable sources.

Today, the MBTA is one of the largest public transit systems in the country, serving nearly 200 cities and towns and over 1 million daily riders on the subway, bus, ferry, and commuter rail.